There’s a term used by magicians to refer to other types of performance which blend well with magic. Things like juggling, ventriloquism, quick change, balloon modelling and shadowgraphy. That term is Allied Arts

Often the allied arts will be included in a gala show at larger magic conventions and they are usually the most popular part. This may be because they are a novel diversion in a sea of magic that all starts to look the same after a while. It may also be because the things defined as allied arts are usually, but not always, overt displays of skill.

A colleague of mine once said that the difference between juggling and magic is that you can see the juggler’s hands. To put it a little more directly: jugglers can make something difficult look easy, magicians can make something easy look impossible¹.

But there’s one magic trick that has its method as clearly visible as juggling or balloon modelling, and yet refuses to be demoted to an allied art, because there’s no overt skill, very little actual skill, and only magicians seem to like it.

But not me.

I cannot fucking stand Troublewit.

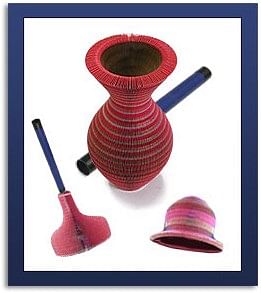

Troublewit, in case you’ve never seen it³ is an effect involving a large carefully pleated piece of paper which may be arranged in a variety of shapes.

That is literally it.

Here, watch someone doing it:

Ah the joys of a captive audience.

Just to be perfectly clear, this is no comment on the abilities of the performer featured there. I picked that video because it is one of the more compelling videos of Troublewit, I’m really trying to steel-man⁴ the case for Troublewit, because I want to go into a bizarre part of my creative process. You might have heard the phrase “don’t yuck my yum” and there’s a very easy going attitude of letting people enjoy whatever they want. If you don’t like it, watch something you like instead and I am here to tell you that this attitude is wrong. As a performer and creative. you should watch things you don’t like. You should watch things you hate.

Often people will tell you to surround yourself with art that inspires you, seek out things you love and use them as a springboard to find your own way. Maybe that works for some people, but what I’ve seen happen time and time again is people finding an act that they love, and being inspired by it to create something almost identical. I’d go so far as to say it’s the reason you see so many copycat magicians performing virtually identical shows⁵. Look at the alternative though, if you can find a routine you hate, everything you change will be an improvement.

How can we apply this process to Troublewit?

Well let’s identify the problems:

- Lack of Context

- Lack of Motivation

- Lack of Spectacle

- Inconsistent Pacing

- Lack of Clarity

- No Build

- No Climax

Lack of Context

Context in this is impossible, because the entire routine is contextualisation effort. The whole performance is explaining what the prop is and what it’s for.

Lack of Motivation

Troublewit can be motivated, but often isn’t. The nature of the routine sets it up like a sales pitch, which is kind of obnoxious and hence very few people use it.

Lack of Spectacle

Can we all agree that there’s no inherent spectacle beyond having remembered the script. We accept that Troublewit is not impossible, not really magic, but also not particularly difficult as the hard part, the origami, is done before the show starts.

Inconsistent Pacing

There’s a pause between the shapes, a pause as each shape is shown, and a longer pause every time a new arm of the Troublewit is extended, which is either filled with incessant jabber or left as dead time. This is a knock-on effect from the lack of motivation, the routine has nothing in the way of a plot to advance. Either way the entire routine is an overt procedural move followed by a display over and over.

Lack of Clarity

The objects formed are largely either unrecognisable, or not easily distinguishable. Without naming them they would be meaningless. If you made all the shapes and took a photo of each then asked people to identify them, they would probably be able to name very few. One day I may attempt an experiment along those lines.

Even aside from this, with maybe two exceptions the objects formed are themselves decontextualised cargo cult icons. The items formed are not really usable as the things they claim to be, indeed they need to be held in place to even retain their form. May of them are vessels that cannot hold water, there is a window you can’t see through, a hat which must be held to the head, the list goes on and on. That’s without even mentioning the fact that some of the references still used are long out of date and out of touch.

No Build

The problem with the sequence is that forming a lampshade from the initial form of the Troublewit and forming a top hat from the last one are essentially identical motions. Part of the unspoken contract with the audience is that if you’re going to do something repeatedly, the iterations get more difficult as you go. Jugglers increase the number of balls, mentalists predict or divine more complex information, magicians allow greater conditions of scrutiny or audience examination.

No Climax

This is sort of the same as the previous point, but even without the build, an effect can have something happen at the end, like a twist or a big finale. Troublewit has no big finale, and the best you can find from the majority of routines that attempt an ending is a joke with some kind of pun on the last object.

So can these be fixed?

The hardest point to fix is motivating and contextualising the objects formed to give them a practical use. If you could do that you could use them for that purpose to overcome a series of problems, like a multitool, which would actually introduce a plot. Unfortunately very few of the Troublewit items are useful or recognisable, so this would require either a more complex prop or considerably fewer items.

Sadly to reduce the time between displays, you would need a far simpler prop. A simpler prop would also enhance the spectacle, as forming complex shapes from a simple prop (rather than the simple shapes from a complex prop of Troublewit as it stands) is at least somewhat impressive.

If the displayed objects had some commonality however, something which more closely tied their utility to their appearance, this might be doable.

It’s also kind of silly to limit yourself to so few hats when the clothing angle has been used elsewhere. The clothing angle is a great idea because so long as you can wear it, the form is the function, as there are hundreds of kinds of hats, many of which have implied characters or roles, which the performer could embody, like a play, with a script, and a build to a dramatic climax…

But this is called chapeauxgraphy and it is considered to be an allied art.

Meanwhile I will share one other routine I found while researching this, a Troublewit routine that solves many of the pacing problems by performing as a double act so one displays while the other does process, carefully choosing which objects to display in what order because the back and forth allows them more time to switch forms. This means they can fit a story of sorts and end with a nice finale as they make two objects which generate interlocking context as they fit together, also a sort of climax.

The only problem is it’s bloody gospel magic.

I still hate Troublewit.

¹ Not all magic is easy, but a surprising amount is not very difficult. Curiously the harder a trick is, the more magicians want to see it, and the less non-magician² audiences appreciate it.

² I don’t use the word ‘muggle’ anymore out of disdain for the author who coined the term.

³ I still remember the golden days when I didn’t know what Troublewit was. Truly a happier time.

⁴ To steel-man is the opposite of straw-man. A Straw-man argument is a weaker misinterpretation of an opponents position which is easy to refute or mock. I could find a bad performance of ANY magic trick and use that to disingenuously say the trick is bad. In this case however I really want to hammer home that troublewit is a routine which, in my opinion, no one can make entertaining to a general audience.

⁵ There is no other fathomable explanation for the sheer number of magicians who strongly associate the sight of snow with a dead grandparent.